Hertz Grosbard (1892-1994) was an actor, word artist, elocutionist, bard and reciter, often called the “Master or Maestro of the Jewish Word” and “Ambassador of Yiddish Literature.” Since the early 1930s he dedicated himself solely to performing word concerts in Yiddish – dramatic recitals of classics of modern Yiddish literature. He toured Europe, North and South Americas, South Africa and Israel, becoming the foremost interpreter of Yiddish literature and a unique one-time phenomenon: a word artist, standing out as the only performer of this kind.

דער מאָדערנער דאַוונער

Hertz Grosbard was born on June 21, 1892 in Lodz, Poland to a Hassidic family. His father, Eliezer, was an Alexander Hassid. His grandfather, Hershl Grosbard, abandoned his business in Warsaw and together with his wife emigrated to Israel where they lived till the end of their days. His maternal grandfather, Avrom Gershon-Morgenstern, was a follower of Gerer Tsadik. Hertz Grosbard received both traditional upbringing and secular education. In his youth, he enrolled into the German Dramatic School in Lodz, affiliated with the Lodz German Theater, and soon after the First World War, he joined the Vilna Troupe in Warsaw in the years 1919-1920 and 1920-1921 as one of the leading (and the oldest) members of the ensemble. He was then part of the next incarnation of the original Vilne Troupe – the Yidish Kinstler Teater in Berlin. He also performed on the German stage, joining such theaters as the Municipal Theater of Frankfurt, the Volksbuehne and the Ervin Piscator Theater in Berlin.

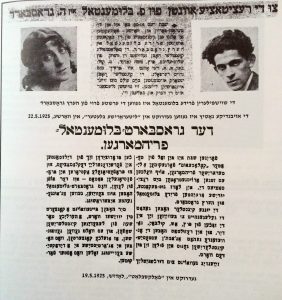

He performed his first “recitation evenings” in 1925, together with his wife Frida Blumenthal, who was also a member of the Vilne Troupe, in Warsaw and Lodz. Year 1928 was transformative for Grosbard. In January, 1928, he was invited to Tshernovitz along with Noah Prilutski, Zalman Reizen, Dr. Tsemakh Shabad, and Dr. Israel Rubin, to perform at the 20th celebration of the anniversary of the Tshernovitz Conference, during which he recited the works of Eliezer Steinberg and Itzik Manger, poets who had been virtually unknown to the audience. Steinberg’s Mesholim (Fables), illustrated by Arthur Kolnik’s twelve woodcuts illustration was published in 1928, inspiring Grosbard to become a life long promoter of Steinberg’s works. Finally, Grosbard gave his first solo word concert on September 18, 1928 in Warsaw.

In the 1930s he went on long word concert tours around the world: in Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, Romania, Germany, Austria, Denmark, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, and South America.

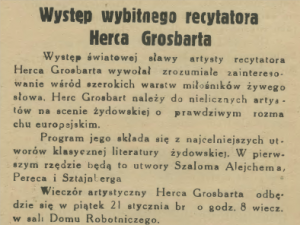

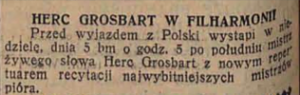

Press announcements of Grosbard’s performances in Philharmonics in Lodz, Poland, February, 1939 (top), and in Workers’ House in Radom in January, 1939 (bottom). According to the Kutno Yizkor Book, Grosbard also visited Kutno in the 1930s. Source: Polish Digital Libraries

He lived in Buenos Aires in the years 1934-1936, and returned there for a word concert tour together with his wife in 1939, three weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War. In South America, he also performed in Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Bolivia. His 50th appearance was celebrated with a publication, Der Mayster fun Yidishn Vort that was issued in Vilnius, Poland.

Posters announcing Grosbard’s concerts in South America [NYPL collection]

In 1951 Grosbard moved to Canada and obtained Canadian citizenship in 1957. In the 1950s and 1960s he toured Canada, the United States, Latin America, South Africa, and Israel. He visited Israel for the first time in 1951, at the invitation of the Habimah, and he gave over 100 concerts during his visit. He also reunited with his actor friends from the Berlin times, Hannah Rovina, Aron Meskin, Shimon Finkel, and Rafael Kliatshkin (Forverts). He returned to Israel almost every year, and eventually moved there with his second wife, Molly, in 1971 and became an Israeli citizen. At the age of 102, he requested to have his last word concert, but he died before it was arranged, on January 2, 1994 in Holon, Israel.

A year after his death, M. Tsanin published a monograph containing press articles, reviews, images, and some personal correspondence of Hertz Grosbard. According to the publisher listed in the book: “Di mi un der onshtreng fun M. Tsanin vi s’iz geven der vuntsh fun Hertz Grosbard in zayn tsavoe,” this impressive monograph was issued by the “labor and effort of M. Tsanin, which was the wish of Hertz Grosbard expressed in his will.” Grosbard’s motivation for the publication was to leave something behind. Writers’ legacy are their books, but what stays behind after an actor or a reciter? He or she lives on in the memories of their audiences but then falls into oblivion (p.9). Tsanin’s monograph offers a wealth of information about the ephemeral artist, Hertz Grosbard.

Critical Acclaim

Hertz Grosbard was a unique phenomenon, a sole reciter and performer of Yiddish literature, and many critics and writers have tried to categorize his art. David Bergelson famously called Grosbard in 1927, the “Modern Cantor of Modern Yiddish Literature … who p r a y s the Yiddish literature” (Bergelson 1927). A renowned Yiddish literary critic, Sh. Niger, described Grosbard as “awakening the respect for the Yiddish word … Each word contains in it a melody (nigun) and the melody has endless incarnations (gilgulim). Each world is potentially a dramatic act” (Forverts). Sh.B. called Grosbard in 1939, “an Ambassador of Yiddish Literature” (Vilner Tog, 1/31/1939), while Dr. Michal Weichert, Yiddish actor and director, credited Grosbard with the invention of the reciting tradition in Yiddish (Undzer Vort, Paris, 1/21/1967). He had no predecessors and followers, he was “one and and only” as Noah Prilutski described him (“Er iz eyner”, Der Moment, 3/14/1936?).

Melekh Ravitsh, Itzik Manger, Tsemakh Shabad, Zalman Reizen, Rokhl Korn, Shmuel Rozhanski, Abraham Lis, A.M.Klein, Aaron Zeitlin and many others wrote about Grosbard, while the Yiddish and Jewish press worldwide followed his every move.

A.M. Klein depicts Grosbard’s art as follows: “Whoever has not heard Hertz Grosbard reading, reciting, elocuting – these verbs are but pale descriptions of his performance – whoever has not heard him rendering from the masterpieces of Yiddish literature, not seen him flash forth his gems, vivify its printed pages, such a one has not ever really known the power and beauty of human expression. To listen to this wizard who turns into magic the simplest of words is an experience.”As one recalls his varied program – monologue, dialogue, mass mise-en-scene, fanciful fable and Hasidic tale, exercise in naivete, nostalgic poem, parody, satire – one hears him again reciting, intoning, whispering, sneering between the hyphens, weeping, almost-weeping, thundering, confiding, even neighing. (Did you ever hear a horse neigh Yiddish? A talking horse? A horse talking Yiddish with inflections truly equine?) Grosbard does all that; and then, in the next poem, he will show you how a sentence actually dreams.”

„גראָסבאַרד איז דער מאָדערנער חזן פֿון דער מאָדערנער ייִדישער ליטעראַטור. … גייט הערן, ווי גראָסבאַרד ד אַ וו נ ט די ייִדישע ליטעראַטור.„

דוד בערגעלסאָן, בערלין-צעלענדאַרף, פֿעברואַר 1927.

„גראָסבאַרד וועקט דרך-ארץ צום ייִדישן וואָרט – און טאַקע אויף דער בינע – דאָס ייִדישע וואָרט איז נישט הפֿקר. יעדעס וואָרט באַהאַלט אין זיך אַ ניגון און דער ניגון האָט אָן אַ שיעור גילגולים. יעדעס וואָרט איז פּאָטענציעל אַ דראַמאַטישער אַקט.„

ש. ניגער

References

Hertz Grosbard’s works:

- Hertz Grosbard, “Arum der oyffirung fun “Dybuk” in poylish teater, Literarishe bleter, 75, 1925.

- Hertz Grosbard: Vort Kontsert, 10 vinyl records, Pleasantville, NY: EAV Lexington, ca. 1950s & 1960s

- Nadirizmen: Aforizmen, Paradoksn, Vertershpil, Poetishe Proze fun Moshe Nadir, selected and edited by Hertz Grosbard, Tel Aviv: I. L. Peretz Farlag, 1973.

About Grosbard:

- Mikhal Ben-Abraham, “Hertz Grosbard: Groyser yidisher vort-kinstler,” Forverts, April 20, 2007

- M. Tsanin, Hertz Grosbard, Tel Aviv, Publisher: Di mi un der onshtreng fun M. Tsanin vi s’iz geven der vuntsh fun Hertz Grosbard in zayn tsavoe, 1995.

- Tsen Yor Hertz Grosbard in Argentine, Buenos Aires: Baerungs-komitet, 1944.

- Hertz Grosbard: Der mayster fun yidishn vort, Vilnius: ZaZyd Towarzystwo, 1938.